Retro Arcade Museum: An Electromechanical Wonderland

By Greg Borenstein on Day 1, March 2010

Yesterday, for day 1, I organized a trip up to the Retro Arcade Museum in Beacon, NY. The museum is filled with arcade cabinets from the 60s and 70s, most of which are electromechanical rather than digital. Together they form a kind of encyclopedia of a lost age of engineering where a vast literature of interactive motion, optical, and sound effects were created using a narrow vocabulary of buttons, relays, cams, lights, and mirrors.

The museum’s proprietor, Fred Bobrow, is an enthusiastic guide to this literature, willing to talk endlessly about all the tricks the games’ designers pulled to achieve their effects. He even opened up a few of the cabinets so we could see how they worked, revealing an amazing universe of magician-caliber optical trickery and incredibly intricate hand-built analog electronic systems.

For this post, I’ll talk about a few of my favorite games and what I learned about how they worked (largely from Fred) and about the aesthetic qualities of their interactions (from playing them).

The first game I played on coming into the museum was Sega’s Gun Fight.

This is a table top format game enclosed in a glass terrine. As you can see, it pits two cowboys together in a pistol duel across an tumbleweed-strewn western town. Each cowboy is positioned behind some cover consisting of a rock wall and two cactuses.

Each player stands behind his cowboy, with his hand on a gun-shaped control, and tries to shoot his opponent when he’s visible through cover, without getting shot himself.

Players can move their cowboys from side to side along the slots beneath them. When you successfully hit another player, their cowboy collapses for a few seconds and your score is increased:

(If you shoot a cactus, it will fall over as well.)

Fred explained that beneath the surface of the machine is a series of lines of contacts. When both cowboys are lined up on the same contact line and one of them presses the trigger, that closes a circuit engaging the solenoid that adds slack to the rubber bands keeping the opposing cowboy standing up (so that the falls down) and causes the next bulb in the score display to light up.

Many games throughout the arcade used this technique of having a series of conductive lines on a circuit board closing a circuit between moving players and targets determine hit accuracy.

The next game I played was Chicago Coin’s Motorcycle:

This game’s main attraction is its beautiful projected graphics. According to Fred, inside the cabinet are a series of three circular zoetrope style screens that spin at different rates to : one with the image for the background (produce the illusion of speed), one with the slower blue riders who appear on the inside of the track, and one with the faster yellow riders who appear on its outside.

These zoetropes all project their figures onto a translucent screen that’s parallel to the floor inside the cabinet at about the height of the player’s controls.

On top of that screen is another motorcycle figure, this one directly connected to the player’s handlebar interface so that it moves side-to-side as the player steers. The final shadowbox image is then reflected by a 45 degree mirror so it can be seen by the player.

The game has a series of electrical contacts connected to the moving player motorcycle and the rotating non-player motorcycles. If any of these touch, a circuit is triggered representing a crash, causing flashing red lights and all of the rotation to stop. Also, there’s another switch that detects each full revolution of the outer zoetrope which counts as the completion of a single lap. For each completed lap, the score counter on the top of the cabinet increases by one via a rotating number connected to a low RPM DC motor.

The player also has an acceleration control on his right handlebar. Turning that causes all of the zoetrope cylinders to spin faster.

The biggest problem with this game is that it is fiendishly difficult. Unless you barely touch the accelerator, the other motorcycles crash into you so quickly that you’re constantly stopped, making for frustrating intermittent gameplay.

The quality and sophistication of the sound used in the games varies wildly from mechanical bells to simple square wave beeping to, surprisingly, pre-recorded sounds.

A great example of the latter is Bally Space Flight:

If you listen carefully over the sound of other games and Hey Jude on the arcade stereo, you can here a series of radio transmission from mission control to the pilot of this lunar lander. These sounds are, amazingly, played via 8-track tapes which are kept in synch with the rest of the gameplay via high pitched noises outside the range of human hearing that are included on the tracks and which are picked up by simple microphones in the analog circuitry controlling the game. The tapes include these sounds every 18 seconds so that the circuitry controlling the downward movement of your space shuttle won’t wander out of phase with the voice of mission control.

Then, the sensors in the game which detect whether you’ve successfully gotten your shuttle’s glowing red landing pod into the hole in each crater, trigger different tapes to play based on whether mission control should be congratulating or haranguing you with “abort” warnings.

One very common technique in these games is the use of beam splitting one-way mirrors to superimpose figures on a scene and to enhance the illusion of depth in the space portrayed inside the relatively small cabinets.

A great example of using mirrors to superimpose moving figures on a static background is Commando:

While it looks like this seascape diorama is located directly in front of you while you’re playing the game, it is, in fact, hidden in a compartment in the body of the cabinet and rotated 90 degrees to the vertical. You see it reflected in a one-way mirror placed at a 45 degree angle in front of you. This setup allows the scene to have more depth than would be possible in the standard 20 inch deep cabinet.

The flying helicopters moving across this landscape are located in the compartment of the cabinet directly in front of the player. They’re lit with black light so that they’ll shine through the one-way mirror without making anything else back there visible.

Part of the purpose of this surprising, but apparently quite common design was to keep cabinets at a size that would allow them to fit through standard doorways while still providing players with a game world that had more than 20 or so inches of depth. Since the games needed to be head and shoulder height anyway, why not take advantage of the optical path created by the long cabinet to enhance the illusion of depth.

Fred explained this principle to us by showing us the insides of Shoot Out, another Western-themed game that takes advantage of this optical path trick to portray a long and dusty western street.

Fred unlocked the bottom of the cabinet and opened the door to show us the saloon at the end of the street upside down in the bottom of the cabinet, facing up towards the one-way mirror.

He then had us look into the main area of the screen while he stuck his hand into the bottom diorama — lo and behold, his fingers descended from the sky of the western street to dance along the top of the saloon!

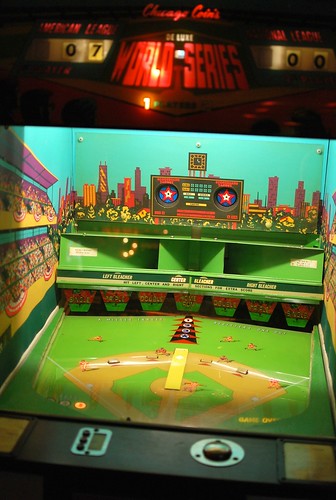

One of the highlights of the trip for me was when Fred opened up the bottom of Chicago Coin’s World Series baseball game to show me the nest of relays, wires, discs, and other mechanisms that make the game go. First, so you can appreciate what’s being achieved, here’s a picture of the game itself:

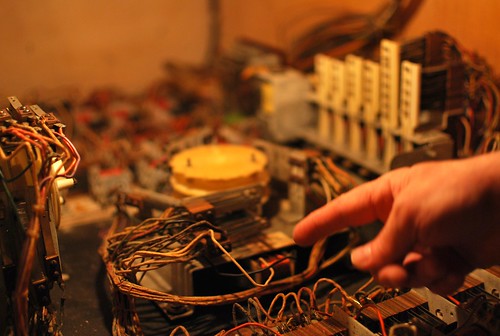

Now, take a look inside:

Here, Fred is pointing out the relay that chooses which type of pitch will be thrown: slider, fastball, or curve. Its settings are controlled by this interface on the top of the game:

The bank of relays and switches on the right of that picture above gets used in resetting the entire state of the game including the number of pitches available to the player and the score.

Here’s a picture of the amazing, early circuit board that serves as the brains of the operation:

Overall, it was an amazing trip and I can’t wait to schedule an appointment to go back and have Fred show me all of the workings of the various games.

The incredible beauty and diversity of the visual and other effects these games with such simple mechanical and electrical systems is deeply inspiring and the actual details of the tricks they use could be a great reference for aspiring physical computing interface designers.

I put a ton more photos and videos in my Retro Arcade Museum set on Flickr. So take a look there if you want to see more. And if you get a chance to drop by the museum, don’t miss it. It’s a truly amazing place.

March 15th, 2010

Leave a Comment

Trackback this post | Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed